GNN Ads

(AsiaTimes.ga) - It is an unlikely friendship that ties the fates of war correspondent Kenji Goto and troubled loner Haruna Yukawa, the two Japanese hostages for whom Islamic State militants demanded a $200 million ransom this week.

Yukawa was captured in August outside the Syrian city of Aleppo. Goto, who had returned to Syria in late October to try to help his friend, has been missing since then.

For Yukawa, who dreamed of becoming a military contractor, traveling to Syria had been part of an effort to turn his life around after going bankrupt, losing his wife to cancer and attempting suicide, according to associates and his own accounts.

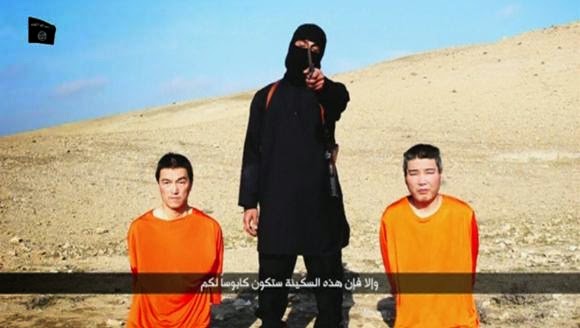

A unit at Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs had been seeking information on him since August, people involved in that effort said. Goto’s disappearance had not been reported until Tuesday's video apparently showing him and Yukawa kneeling in orange t-shirts next to a masked Islamic State militant wielding a knife.

Yukawa first met Goto in Syria in April and asked him to take him to Iraq. He wanted to know how to operate in a conflict zone and they went together in June.

Yukawa returned to Syria in July on his own.

"He was hapless and didn't know what he was doing. He needed someone with experience to help him," Goto, 47, told Reuters in Tokyo in August.

Yukawa's abduction that month haunted Goto, who felt he had to do something to help the man, a few years his junior.

"I need to go there at least once and see my fixers and ask them what the current situation is. I need to talk to them face to face. I think that's necessary," Goto said, referring to locals who work freelance for foreign correspondents, setting up meetings and helping with the language.

Goto began working as a full-time war correspondent in 1996 and had established a reputation as a careful and reliable operator for Japanese broadcasters, including NHK.

"He understood what he had to do and he was cautious," said Naomi Toyoda, who reported with him from Jordan in the 1990s.

Goto, who converted to Christianity in 1997, also spoke of his faith in the context of his job.

"I have seen horrible places and have risked my life, but I know that somehow God will always save me," he said in a May article for the Japanese publication Christian Today. But he told the same publication that he never risked anything dangerous, citing a passage in the Bible, "Do not put the Lord your God to the test."

In October, Goto's wife had a baby, the couple's second child. He has an older daughter from a previous marriage, people who know the family said.

Around the same time, he made plans to leave for Syria and uploaded several short video clips to his Twitter feed, one showing him with media credentials issued by anti-government rebels in Aleppo.

On Oct. 22, he emailed an acquaintance, a high school teacher, to say he planned to be back in Japan at the end of the month.

Goto told a business partner with whom he was working to create an online news application that he expected to be able to travel in territory held by the Islamic State because of his nationality.

"He said that as a Japanese journalist he expected to be treated differently than American or British journalists," Toshi Maeda said, recalling a conversation with Goto before his departure for Syria. "Japan has not participated in bombing and has only provided humanitarian aid. For that reason, he thought he could secure the cooperation of ISIS."

Friends say Goto traveled from Tokyo to Istanbul and traveled from there to Syria, sending a message on Oct. 25 that he had crossed the border and was safe.

"Whatever happens, this is my responsibility," Goto said on a video recorded shortly before he set out for Raqqa, the capital of the Islamic State.

That was the last time he was seen before the IS video this week.

(Additional reporting by Nobuhiro Kubo, Teppei Kasai and Mari Saito; Editing by Will Waterman and Raju Gopalakrishnan)(GA, Reuters)

Yukawa was captured in August outside the Syrian city of Aleppo. Goto, who had returned to Syria in late October to try to help his friend, has been missing since then.

For Yukawa, who dreamed of becoming a military contractor, traveling to Syria had been part of an effort to turn his life around after going bankrupt, losing his wife to cancer and attempting suicide, according to associates and his own accounts.

A unit at Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs had been seeking information on him since August, people involved in that effort said. Goto’s disappearance had not been reported until Tuesday's video apparently showing him and Yukawa kneeling in orange t-shirts next to a masked Islamic State militant wielding a knife.

Yukawa first met Goto in Syria in April and asked him to take him to Iraq. He wanted to know how to operate in a conflict zone and they went together in June.

Yukawa returned to Syria in July on his own.

"He was hapless and didn't know what he was doing. He needed someone with experience to help him," Goto, 47, told Reuters in Tokyo in August.

Yukawa's abduction that month haunted Goto, who felt he had to do something to help the man, a few years his junior.

"I need to go there at least once and see my fixers and ask them what the current situation is. I need to talk to them face to face. I think that's necessary," Goto said, referring to locals who work freelance for foreign correspondents, setting up meetings and helping with the language.

Goto began working as a full-time war correspondent in 1996 and had established a reputation as a careful and reliable operator for Japanese broadcasters, including NHK.

"He understood what he had to do and he was cautious," said Naomi Toyoda, who reported with him from Jordan in the 1990s.

Goto, who converted to Christianity in 1997, also spoke of his faith in the context of his job.

"I have seen horrible places and have risked my life, but I know that somehow God will always save me," he said in a May article for the Japanese publication Christian Today. But he told the same publication that he never risked anything dangerous, citing a passage in the Bible, "Do not put the Lord your God to the test."

In October, Goto's wife had a baby, the couple's second child. He has an older daughter from a previous marriage, people who know the family said.

Around the same time, he made plans to leave for Syria and uploaded several short video clips to his Twitter feed, one showing him with media credentials issued by anti-government rebels in Aleppo.

On Oct. 22, he emailed an acquaintance, a high school teacher, to say he planned to be back in Japan at the end of the month.

Goto told a business partner with whom he was working to create an online news application that he expected to be able to travel in territory held by the Islamic State because of his nationality.

"He said that as a Japanese journalist he expected to be treated differently than American or British journalists," Toshi Maeda said, recalling a conversation with Goto before his departure for Syria. "Japan has not participated in bombing and has only provided humanitarian aid. For that reason, he thought he could secure the cooperation of ISIS."

Friends say Goto traveled from Tokyo to Istanbul and traveled from there to Syria, sending a message on Oct. 25 that he had crossed the border and was safe.

"Whatever happens, this is my responsibility," Goto said on a video recorded shortly before he set out for Raqqa, the capital of the Islamic State.

That was the last time he was seen before the IS video this week.

(Additional reporting by Nobuhiro Kubo, Teppei Kasai and Mari Saito; Editing by Will Waterman and Raju Gopalakrishnan)(GA, Reuters)